anastasia kārkliņa June 16 · 7 min read

anastasia kārkliņa June 16 · 7 min read

I was swiping through Instagram stories when I saw a humorous Tik Tok video poking fun at the pressure that many parents feel to stay calm when disciplining their children in public. Embarrassed, they timidly smile at onlookers and diplomatically negotiate with their screaming kid, only to blow up with rage and reach for the belt as soon as they make it into the doorway. It seemed like befitting content in these pandemic times as stressed, overextended parents are forced to work and homeschool at once. Perhaps, for others, it was a short comedic relief from the stream of rage-inducing news about yet another police killing, a rapid rise in coronavirus cases, and an unemployment rate of historic proportions. Yet, as I replayed this seemingly innocent video over and over again, I thought just how precisely a joke about hitting children shows what those who are skeptical about police abolition fail to understand.

At first glance, corporal punishment and child abuse seem hardly related to the issue of police violence and the Black Lives Matter movement’s demand to defund and abolish police in the United States. At the very core, however, both of these social issues are rooted in the same cultural logic of punishment that has been completely normalized in our society.

Whether we hit children into submission, violate—if not murder—a “criminal suspect,” or put masses of people in prison cells, the unspoken assumption is all the same: the act of violence is a punishment, and it is an earned consequence that the wrongdoer must endure and suffer in silence in order to correct and socially atone for negative behaviors.

We see this in the way that many people desperately look for ways to justify indefensible slayings of black people like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Eric Garner, and many more. The long-standing cultural belief that people are subjected to deadly violence or coercive force by law enforcement because they did something to merit such a punitive response is deeply engrained not only in our social institutions (like the police or prisons) but in the cultural imagination itself.

For many, being confronted with the idea that people are subjected to violence in our society because this is how our culture teaches those with power to control others is deeply uncomfortable. Seeing the use of violence as gratuitous, rather than merited, fundamentally unsettles the way in which carceral culture socializes Americans, and especially whites, to think about themselves and the social institution of policing tasked to “serve and protect” them.

Conceptually, the idea of violence as a mechanism by which society is disciplined shatters the illusion of a distinction between “good” and “bad” people and threatens our psychological investment in ideas like morality, goodness, and safety that are framed precisely in terms of these binaries. The enigmatic figure of the (black) criminal must exist so that we can be assured that “we” are not like “them” and that what happens to them cannot and should not happen to “us.”

The impulse to defend and justify how violence is weaponized to control, surveil, and dominate oppressed people shows that violence is considered to be an integral part of our cultural communication and a legitimate means of settling interpersonal disputes, particularly misbehavior. We’ve heard it all before, maybe at our own dining table or from the nearby office cubicle. “Well, wasn’t he trying to spend a counterfeit $20 bill?” “He was no angel selling untaxed cigarettes!” “It wouldn’t have happened if he didn’t start running away.” Perhaps, we have, at some point, said it ourselves.

As such, the need to frame violence against victims as warranted punishment extends far beyond the issue of racist policing. Most of us pick up on and internalize such violent ways of relating to each other early on in life. We quickly learn that some people “deserve” to be punished (with violence, bullying, silence, or indifference) simply because they have, in one way or another, overstepped the unspoken social mandate. We label people “criminals” if they have broken the rule of property law, but they need not break legal boundaries to be cast outside of social belonging. Consider all the ways in which over the years immigrants, Muslims, and, with the coronavirus pandemic, Asian Americans, too, have been ostracized, harassed, and even physically attacked simply because they are perceived as a threat to the security and wellbeing of Americans.

It is hardly surprising that cultural narratives of punishment are so well-established, since we are taught to think of violence as legitimate punishment since childhood. Despite the popular adage “violence is never the answer,” the vast majority of us learn not only to tolerate but to accept violence as a normal part of everyday life through our first experiences in the family structure. bell hooks contends that social violence begins with patriarchal conditioning within the home. “Patriarchal violence in the home,” she writes, “is based on the belief that it is acceptable for a more powerful individual to control others through various forms of coercive force.” This applies not only to the dynamic between romantic partners, she notes, but to the relationship between the caregiver and the child.

If we are not “disciplined” through violent physical and emotional abuse as children, then most of us have been at least put in the corner, shamed or in some other way isolated from others as punishment. Whenever the issue of child abuse comes up, people routinely jump up with defensive arguments about how violent discipline is necessary in order to raise polite and respectable children, despite years of research that completely disputes the effectiveness of physical punishment. Nevertheless, it is still widely assumed that “disciplining” children using physical and emotional punishment will teach them the life lessons they need to grow into responsible “good” adults.

However, if we fail to learn the lesson when we grow up, the metaphorical “reflection” corner where the young child stood—punished, shamed and isolated from others—becomes the jail cell. Law enforcement authorities mimic the patriarchal rule established in the family unit on a national scale. Just like the parent who treats the child with a sense of power and the right to punish for the sake of “discipline,” the state assumes the role of the benevolent disciplinarian over its population in the name of “order.”

Despite the ample evidence to suggest that economic poverty, substance use disorders, and lack of economic opportunities trap oppressed communities in cycles of criminalization, in a patriarchal culture the wrongdoers, like children, are penalized, isolated, and put away to reflect on their misdeeds, rather than rehabilitated and aided in regaining control over their lives. They should have, after all, made “better choices.”

All this is to say that the way we are taught to relate to another—ultimately, fearing each other and deriving a sense of comfort that those who so terrify us are kept under control—deeply shapes how our culture determines who is deserving of punishment and who is entitled to enact it. In every aspect, we live in a culture of violence.

More than that, how we think about harm and punishment has profoundly shaped social practices, public policies, and budget priorities, such that in the United States there are more police in schools than counselors, 250% more prison cells than hospital beds, and 28 states with death penalty laws.

So, as abolitionists, we want to call attention to the way in which we have accepted and taken for granted this system of enormous violence and punishment as the primary and only way of living with others.

Rooted in the history of black resistance practices, the abolitionist movement looks to shift these cultural norms towards embracing notions of healing, compassion, and holistic justice as equally viable paths for nurturing a society in which all people are free from fear and domination.

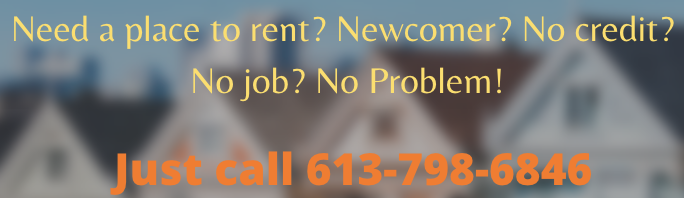

Abolition calls forth a world where each and every one of us has a birthright to be our whole selves and live in full dignity. Therefore, in calling for defunding the police and investing in communal wellness, abolitionists offer a fundamentally different model for thinking about human interconnectedness and social belonging. Instead of punishing, policing, and locking communities in cycles of violence, we can choose to center the ethos of radical love and collective care by providing our communities with compassion, dignity, and financial resources that would lay ground for stable access to safe and affordable housing, education, healthcare, and economic opportunities.

Abolition challenges the limits of our imagination and calls on our inherent capacity to imagine otherwise—to think outside of the regime of violence and to envision alternative ways of being in this world. Abolishing policing is a necessary step towards ending four centuries of racial violence against black people but it is only the beginning. To build truly anti-racist, feminist social structures that work for and empower all of us, we must radically shift and re-imagine how we relate to each other. As prolific black feminist abolitionists Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba teach us, we must heed the call and decriminalize our imagination by not merely dreaming or wishing for change but actively working towards the kind of world that we know, with all of our being, is possible.

This post was curled from the Medium